Unveiling the Sacred: Exploring the Harshatmata Temple of Abhaneri

By Srija Sahay

Abaneri, or Abhaneri, is a popular tourist spot in Rajasthan, located off the Delhi-Jaipur highway. It boasts one of India's deepest stepwells, the Chand Baori. The site is also home to the 9th-century Harshatmata Temple. During his 19th century survey of Rajasthan, James Tod came across the ruins of an ancient structure of importance in a small village called Abhanair, three miles from Lalsot. The bards, who sang tales of Raja Chand and Permala's romance, had already made the place known. The Harshatmata Temple then came to the attention of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), and the site later made its way into the Jaipur Circle's selection of important monuments in 1925 CE. The temple's restoration began in the 1940s, under the direction of Satya Prakash.

Abhaneri is renowned for its exquisite sculptures, said to draw inspiration from the Gupta era of art. Some selected sculptures received scholarly attention from R.C. Agrawala, Pupul Jayakar, and Neelima Vashishtha [1]. Rajendra Yadav [2] and Cynthia Packert Atherton [3] have made significant contributions to the art and architecture of the site, which form an important part of the site's historiography. Only a few sculptures remain in situ at the temple, while the majority of the recovered sculptures are housed in an enclosure at the Chand Baori. Various museums and private collections, including the National Museum in Delhi, the Hawa Mahal in Jaipur, the Albert Hall Museum in Jaipur, and the private collection of the Maharaja of Jaipur, also display many of these sculptures. Due to a lack of foundational inscriptions at the site, tracing the temple and stepwell patrons is difficult. However, the iconographies at the site reveal multiple clues to possible patronage and the sectarian beliefs of these patrons.

The Harshatmata Temple

The site, built in the 9th century CE Maha-Maru style, presents exquisite specimens of post-Gupta developments in art and architecture. In plan, the temple is tri-anga (with three offset planes) and pancha-ratha (with five offsets from kona to kona on a given side). While not much remains intact on the site, the temple’s stylistics, as well as inscriptions from the Shakambhari dynasty, reveal clues to the sectarian worship prevailing at the site. The Harsha stone inscription of Vigraharaja and the Bijholi inscription of Somesvara mention the Shakambhari Chahamanas as descended from Vasudeva, with Shakambhari Devi as their patron goddess. [4] According to the inscriptions, Shakambhari Devi is also considered a consort of Vishnu, and the dynasty further claimed descent from the ‘right eye of Vishnu’. The depictions of Pradyumna, Aniruddha, and Sankarshana Balarama on the vedibandha (mouldings at the base of the temple wall) indicate Pancharatra worship of Vaikuntha Vishnu. The Pancharatra cult is one of India's oldest surviving Vaishnavism sects today, and its influence covered northern, western, and central India during the early medieval period.

Pancharatra is a tantric form of Vishnu worship. The sect prophesies the existence of an all-inclusive God who is imminent and antaryami (all knowing). The main tenets of Pancharatra describe Vasudeva as the central deity, who manifests when combined with his Shakti for the divine creation of the universe.[5] The followers of this sect heavily rely on the emanatory concept in their cosmogonic mythology, where the Bhagvata is the culmination of all gunas (attributes), and the separation of these gunas forms the vyuhas (emanations) that explain cosmic activity. As a result, the philosophy is centered on emanations, primarily represented by members of the Vrishni family. [6] On the base mouldings of the bhadra (central projection typically to one of the cardinal directions) walls, Samkarshana faces north, while Pradyumna and Aniruddha face west and south, respectively. (Image 1, 2, 3) Since the directional arrangement violates the natural progression of the emanations of Vishnu from Vasudeva to Samkarshana to Pradyumna and Aniruddha, Cynthia Packert Atherton argues that the temple’s layout depicts the journey of the practitioner from the unmanifest to the manifest in reverse order. However, the placement of the vyuhas does not conform to clockwise or anti-clockwise movement, disturbing the potency of tantric worship. The reason for this placement, intentional or otherwise, cannot be discerned. Perhaps the artists were unfamiliar with the sect that became popular in the 11th century CE. However, we cannot ignore the presence of Pancharatra at the temple in favor of the numerous sculptures of Shakti.

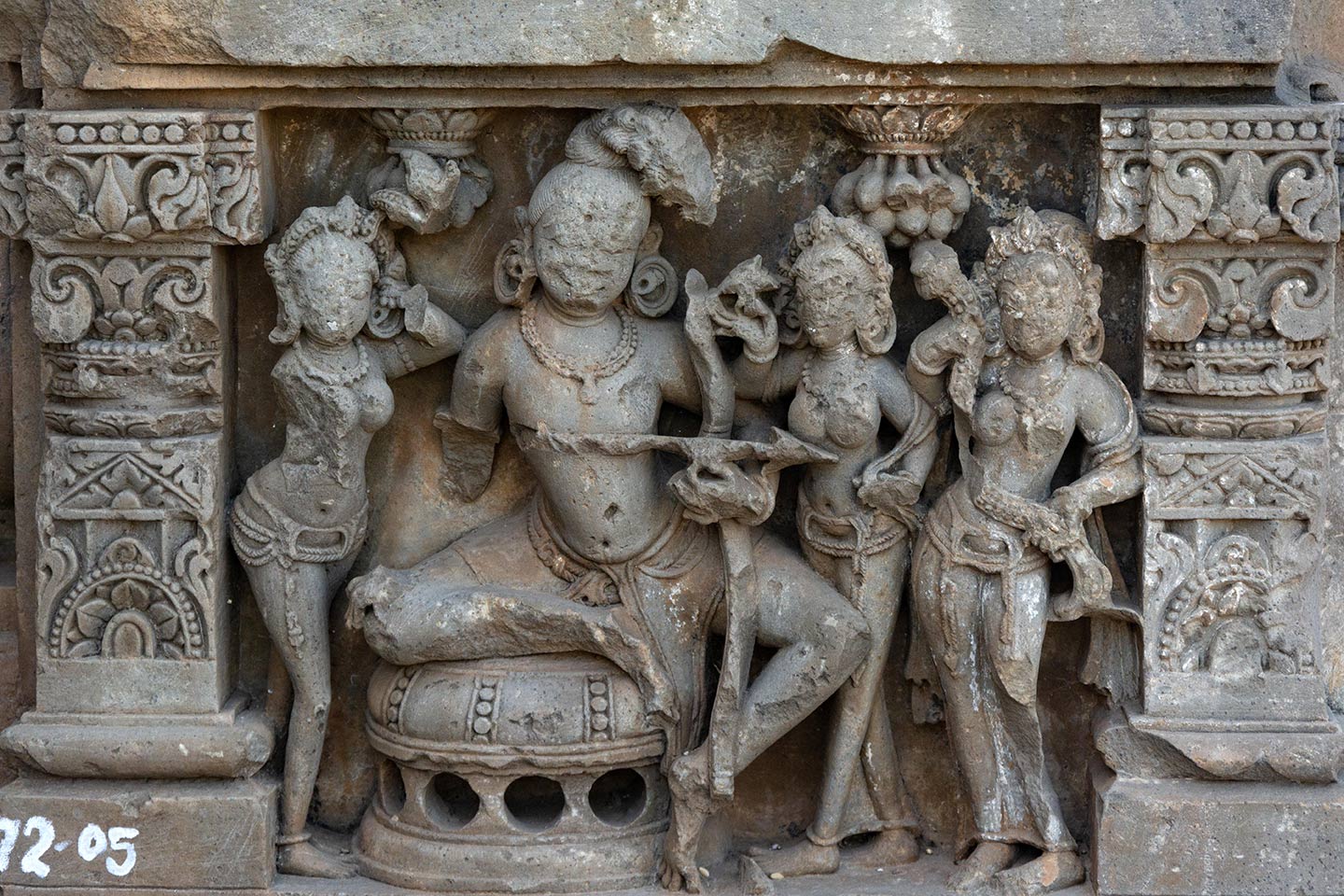

A few sculptures remain at the mancha (dias) level and in the gudhamandapa (closed hall), despite the temple retaining much of its original artwork. Elegant representations of courtly leisure, with female companionship in various poses, convey the many stages of romance and courtship. The representation of couples at Abhaneri is restrained and not explicit, contrasting with later norms from the 10th century CE onwards. A possible representation of Kamadeva is also present at this level (Image 4). The sculptures in the gudhamandapa depict scenes of daily worship, as well as Vishnu's various avataras (manifestations). The representation of Krishna-Lila also fits well with the Pancharatra scheme, as does the large sandstone image of Krishna-Govardhana found among the loose sculptures at the Chand Baori enclosure. The Kaliyamardana episode depicts Krishna riding Kaliya, while the Keshinisudana tale depicts an encounter with the Kesi demon. Other avataras include Narasimha, Trivikrama Vishnu, Varaha, and Aniruddha. The gudhamandapa also depicts sculptures of Surya, Shiva, and Shiva as Natesha, along with a scene of linga worship. The garbhagriha (sanctum sanctorum) lacks the lalatabimba (lintel), and mortar has plastered its space in its place. However, the Hawa Mahal Collection, Albert Hall Museum, and the National Museum have recovered and displayed lintels from the site. Reading these lintels, along with those kept in the Chand Baori enclosure, indicates the presence of multiple sects. A female attendant serves Kubera wine in the center of the panel from Hawa Mahal, which depicts a gay scene of musicians and dancers. The left section also displays Durga in a padmasana posture (Image 5). The Saptamatrika panel from the Albert Hall Museum showcases intricately detailed matrikas, or mother goddesses, each with their unique vahanas, or mounts, centered around Vinadhara Shiva (Image 6). Another lintel from the National Museum shows a trishaka panel with Shiva and Parvati in alingana (embrace), interspersed with kirtimukhas (face of glory) (Image 7). R.C. Agrawala mentions a lintel featuring Vishnu at its center, placed above a principal niche outside of the main shrine. [7] However, this lintel is currently missing. Other panels include an elaborate depiction of the devasura-sangrama, inspired by the Devi Mahatmya, as well as a depiction of the Tridevas.

The site has yielded numerous loose sculptures, including beautiful examples of Krishna Govardharna, Yoga Narayana, Balarama, Surya, and Kubera, along with Shiva Andhakasura-vadha murti, Isana, and multiple images of Karttikeya and Ganesha. The site features multiple sculptures of Durga Mahishasuramardini and Chamunda, along with Kshemankari and Parvati, despite the Pancharatra influence evident in the temple's iconographic scheme. The miniature shrines at the stepwell also display Mahishasuramardini and Ganesha in niches dated to the 9th century CE. The iconography of Kshemankari and Chamunda at the site is clearly a later development and bears similarities to those found at the 10th century Ambika Temple in Jagat. Kshemankari is a goddess who provides protection to travellers and is significant in tantric worship as she emanates the syllable ‘kshe’ as a mantric tool. The depiction shows her holding a book, symbolizing supreme knowledge in a codified format. Her depiction is benevolent, as opposed to Chamunda, who embodies the ferocious aspect of Shakti (Image 8). The depiction of Chamunda with her charchika (little finger) raised to her lips is symbolic of the events that led to Raktabija's death (Image 9). The 10th century CE also witnessed a later development of this symbolic nature at Jagat. The combination of Chamunda, Kshemankari, and Durga Mahishasuramardini can also be found at the Sacchiya Mata Temple in Osian. [8] The loose sculptures also contain two fragments of a life-sized Mahishasuramardini sculpture. Interestingly, Satya Prakash's restoration record talks about worshipping a broken Durga Mahishasuramardini idol in the sanctum. These pieces found at the Chand Baori could also have been meant for sanctum worship, even though they don't show any signs of ritual veneration. [9] The fragmented evidence suggests a shift in worship patterns around the 10th century CE. This theory is supported by the loose shurasenas (antefix above the roof) with depictions of Shiva and Durga. The site also presents evidence of Jaina presence, including a life-sized sculpture of Parashvanath sitting on a bed of snake coils, echoing the Gupta-period Sheshashayi Vishnu at Deogarh, albeit fragmented. [10] The site also contains a smaller architectural fragment of Jina in the Kayotsarga mudra. An independent shrine between the Harshatmata Temple and the Chand Baori now houses a Mahavira sculpture, currently venerated as Hanuman, indicating a modern appropriation of Jain imagery. The exact timing of this conversion is unclear.

Patrons of the Harshatmata Temple and Chand Baori

The information bulletin by ASI attributes the patronage of the temple and the stepwell to Raja Chand of the Nikumbha Dynasty. James Tod’s records also reference Raja Chand and Permala. The narrative narrates the love affair between Raja Chand of Abhanair and Permala, who had a betrothal to Raja Sursen of Indrapuri, a location Tod speculates could be Delhi. This affair sparked a bitter rivalry between the two kings. [11] Local lore also connects both the village and the temple with the illustrious Raja Bhoj and Raja Chand, and the villagers sing'shahara ghadhi pargana, Alwar gadha ke pas; basti Raja Chand ki, Abhaneri nivas’. This testament to the enduring nature of memory highlights its importance in the realm of popular history. Despite possible distortions, Raja Chand's legacy has deeply ingrained itself into the very essence of the village, persisting to this day.

However, upon closer examination, the identity of Raja Chand beyond the bardic narratives remains elusive. In his analysis of the various dynasties mentioned in the Kanhadadeprabandha, Dasratha Sharma notes that although the list of 36 dynasties includes the Nikumbhas, it does not name any specific kings. Moreover, during this period, the region was under the rule of the Shakambhari Chahamanas, who were the feudatories of the Gurjara-Pratiharas. [12] The in-situ sculptures of Samkarshana Balarama, Aniruddha, and Pradyumna at the vedibandha level underscore the site's connection to Pancharatra worship of Vaikuntha Vishnu, a worship style exemplified at Khajuraho's renowned Lakshmana Temple during the reign of Yashovarman of the Chandela dynasty. Temples dedicated to Vaikuntha Vishnu, often sponsored by dynasties previously under Gurjara-Pratihara dominance, serve as focal points for studying the sectarian influence networks within regions linked by vassal-overlord ties. Chandraraja II, a Shakambari ruler who was contemporaneous with the temple and stepwell's construction, emerges as a potential patron. Inscriptions such as the Bijholi Rock Inscription of Chahamana Somesvara and Yashovarman’s foundational inscription of the Laksmana Temple help in narrowing the identity of possible patrons of the site. Furthermore, the stepwell underwent restoration and expansion in the 18th century CE under the leadership of Sawai Jai Singh of Amer. [13] Two figures are proposed as likely identities of ‘Raja Chand’. Jai Singh had married princess Chandra Kunwar of Udaipur with the understanding that she would be the chief queen of Amer, hold a higher rank than any other women he would marry, and ensure that any sons born from this union would be the first in line to succeed. Thus, Jai Singh vested Princess Chandra Kunwar with immense powers, and given the traditional association of stepwells with women in power, Chandra Kunwar could potentially serve as a patron. Rama Chandra Pant, the Diwan of Amer, can also be considered the legendary ‘Raja Chand’, if one is to draw a comparison with the bard song recorded by Tod. Diwans maintained general supervision over the state's daily affairs, as well as the activities of various departments. This hypothesis places the Sawai Jai Singh period as the most probable time for the renovation of the stepwell. A curious incidence is the similarity of the name, both in the case of Shakambhari Chahamanas as well as in the 18th century.

The Local Connection

The locals have a keen sense of their area's history, frequently sharing legends and perceptions related to the temple and the stepwell complex. These tales frequently attribute the destruction of the complex to historical figures like Muhammad Ghori or Emperor Aurangzeb. There is a widespread belief among the community that a hidden treasure of gold lies within the depths of the stepwell. Tales of secret tunnels, purportedly used by queens for escape, popularize the site and provide an explanation for the stepwell's current inaccessible state. Myths and legends surround the temple as well.

The region is characterised by a strong sense of social identity, particularly evident in the practices surrounding the temple worship. Brahmanas from the Barthara, or the Barthaeda gotra, have assumed the responsibility of daily worship at the temple. This tradition continues today, with the family currently in seva (service) Harshatmata, or Harasiddhi Devi—as indicated by the sign at the temple entrance—belonging to the same gotra. This brahmana family originally received the land in muafi (a tax-free grant) from the village monograph, but the state government has since re-acquired it instead of cash compensation. Despite these changes, the right to claim offerings remains with the priest, reflecting a lineage of service that spans generations. This family's ancestral ties to the temple, their ongoing role in its management and worship, and the expectation that their descendants will continue in this role underscore a deep sense of continuity and connection. This sense of permanence and continuity in posterity is an important aspect of both the temple's history and its worshippers' identities, weaving together the community's present with its past in a shared narrative of enduring devotion.

The daily lives of the people at Abhaneri revolve closely around the temple, which serves as the central hub for various rituals marking an individual's significant life events. The 'Jaddula' ceremony, a variation of the'mundana' or head-shaving rite, involves preserving and depositing clumps of hair from a child's head into the temple of the family deity. People stuff these clumps into the gavaksha (decorative motif in the shape of a cow eye or sun ray aureole) niches on the walls of the Harshatmata Temple, believing that close proximity to the Goddess confers her protection. Ceremonial expenses for such rituals account for nearly fifteen percent of the total village expenditure.

Additionally, the temple is a jatra (pilgrimage) site. In Rajasthan, jatra typically refers to a pilgrimage to local shrines, as opposed to the more formal yatra, which involves travel to major tirthas such as Badrinath Dham in Uttarakhand or Jagganatha Puri, among others. These jatras facilitate negotiations between devotees and their chosen deity. When the deity fulfills their requests, devotees anticipate reciprocating with specific acts. [14] For instance, people often seek employment as a reward for making offerings to the deity or the temple. Harshatmata is renowned for granting desires, attracting local visitors seeking various blessings. If a person fails to fulfill their vow, they will also face punishments. People also approach the Goddess for issues like barrenness, which they believe stems from the anger of the pitra (ancestors) or the kula-devi-devata (ancestral deities). Devotees approach Harshatmata, the ishta (chief deity) of the village, for fertility blessings, promising reciprocal acts of devotion in exchange for the boon. In order to have children or prevent infant deaths in the family, devotees offer liquor to either Harshatmata or Bhairodeva. The Bhairo Temple, located near the Harshatmata Temple, is particularly known for fierce retribution in cases of unfulfilled vows. Additionally, the temple is believed to offer protection against the 'evil eye,' a common concern among devotees.

The temple site's socio-religious and economic significance is further exemplified by the numerous celebrations held throughout the year. For instance, the temple site celebrates Navratri with grandeur and organises fairs. During this period, the temple activities blend traditional puja paddhati with local flavour. The recitation of the Durga-charita through the Saptashati path (ceremonial recitation of Saptasati) in Sanskrit is a cherished ritual, and the evenings see a mandali (groups) of local women singing bhajans (devotional songs), often featuring religious renditions of popular movie songs accompanying the dholki, khadatala, and chimta. A fair, albeit with a small attendance of approximately a hundred and fifty people, is also organized. At the conclusion of the nine-day festival, the jvari (khetri or paddy grown for navratri) that was sown at the start of the festival has grown, symbolising the fertility bestowed upon the family by the goddess. People preserve portions of this crop as blessings of prosperity and offer the remainder at the base of the peepal tree. Large crowds attend the popular three-day Harshat Mata ka Mela fair. Another significant festival that ties the stepwell and the temple together is the Jal-Jhulani gyaras, or ekadashi, which is popularly celebrated in various parts of Rajasthan.

The temple's "living" status provides insight into how we interact with the past. It extends beyond merely gaining a ‘historical sense’ of the monument to encompass perceptions of it. What remains in the public's collective memory is how their ancestors worshipped and engaged with the temple. Stories abound about the days when the stepwell was open for exploration, remembered as a space for childhood adventures. Tales of ghosts and djinns, as well as the theft of a blue sapphire idol that was worshipped in the sanctum—though unseen by anyone—are ingrained in the temple's popular memory. As a result, the people's engagement at Abhaneri, where tourism is critical, differs greatly from the archaeological approach.

The temple priest at Abhaneri passionately advocates for the site's renovation, believing it could become one of Rajasthan's most magnificent structures. [2] However, the ASI prohibits interventions that compromise historicity. The site's preservation plays a crucial role in establishing a connection between its potential patron and the socio-political context of its construction period. Yet, preservation should extend beyond the enclosure, including a multitude of sculptural fragments that lie exposed in the sun around the temple boundary. This raises the question of what should be preserved. The scattered sculptures in museums also fail to provide contextual information, resulting in isolated meanings. As a built space, the temple necessitates engagement with past and present contexts, both local and traditional, in order to gain a holistic understanding of the structure's significance in the modern world.

Footnotes:

[1] Vashishtha, Sculptural Traditions of Rajasthan.

[2] Yadav, The Sculptural Art of Abaneri.

[3] Packert-Atherton, ‘The Harṣat Mātā Temple at Ābānerī,’ 201-236.

[4] Keilhorn, Harsha Stone Inscription of The Chahamana Vigraharaj, vol. 14, 116–130.; also see- Vyās, Bijholi Rock Inscription of Chahamana Somesvara, vol. 26, 84–112.

[5] Gupta, ed., ‘The Pāñcarātra Attitude to Mantra,’ 225.

[6] Sahay, ‘Connected Worship: Locating Pāñcarātra Networks in Western and Central India,’ 313–328.

[7] Agrawala, ‘Sculptures from Ābānerī Rajasthan,’ 134. While the accession number of the sculpture (AB/10/150) is known, the sculpture or its image could not be traced.

[8] Srija Sahay, ‘The Divine Feminine at Abhaneri’.

[9] Prakash, As Stones Speak: Abhaneri, 5.

[10] Personal Conversation with Prof. Parul Pandya Dhar, Professor of History of Art of South and Southeast Asia, University of Delhi.

[11] Tod, Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan, vol. 2, 313–314.

[12] Sharma, Early Chauhān Dynasties, 271–272.

[13] Bhatnagar, Life and Times of Sawai Jai Singh, 28. Jai Singh was given the Pargana of Abhaneri.

[14] Gold, Jātrā, Yātrā and Pressing Down Pebbles, vol. 1, 82.

[15] Personal conversation with Mr Sunil Panda, the priest at Harshatmata Temple.

Bibliography:

Bhatnagar, V. S. Life and Times of Sawai Jai Singh, 1688-1743. Delhi: Impex India, 1974.

Gold, Ann Grodzins. Jātrā, Yātrā and Pressing Down Pebbles: Pilgrimage within and beyond Rajasthan. Vol. 1 of The Idea of Rajasthan: Constructions, edited by Karine Schomer, Joanne L. Erdman, Deryck. O. Lodrick, Llyod I. Rudolph. AIIS, 1994.

Gupta, Sanjukta. The Pāñcarātra Attitude to Mantra, Understanding Mantras. Edited by Harvey P Alper. State University of New York Press, 1989.

Keilhorn, F. ‘Harsha Stone Inscription of The Chahamana Vigraharaja.’ In Epigraphia Indica 14, edited by F W Thomas. Bombay: British India Press, 1917–18.

Packert-Atherton, Cynthia. ‘The Harṣat Mātā Temple at Ābānerī: Levels of Meaning.’ In Atribus Asiae 55, no. 3/4 (1995): 201-236

Sahay, Srija. ‘Connected Worship: Locating Pāñcarātra Networks in Western and Central India.’ Journal of Dharma Studies 4, (2021): 313-328.

Sharma, Dasharatha. Early Chauhān Dynasties. Ahmedabad: Books Treasure, 1959.

Tod, James. Annals and Antiquities of Rajasthan or The Central and Western Rajpoot States of India Vol 2. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, 1832, 1957.

Vashishtha, Neelima. Sculptural Traditions of Rajasthan (Ca. 800-1000 AD). Jaipur: Publication Scheme, 1989.

Vyās, Pt. Akshaya Keerty. ‘Bijholi Rock Inscription of Chahamana Somesvara.’ Epigraphia Indica 26, edited by N. P. Chakravarti. Delhi: Manager of Publication, 1938, 1941.

Yadav, Rajendra. The Sculptural Art of Abaneri: A Paradigm. Jaipur: Jawahar Kala Kendra, 2006.