Chand Baori: Exploring the architectural wonder of Abhaneri

By Srija Sahay

Of the many monuments present in Rajasthan, the Chand Baori is one of the most popular destinations for tourists. Located at an accessible distance from Delhi, the stepwell is considered to be the deepest in the region. B.L. Dhama's 1925–26 Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) exploration report, which mentions the stepwell's location in the southwest corner of Abhaneri village and the presence of two beautiful images of Durga Mahishasuramardini and Ganesha, offers scant details. [1] It is believed to have been constructed contemporaneously with the adjacent Harshatmata Temple, and the location of the stepwell should be taken into account when considering the site as a whole. The deity Varuna, closely associated with various aspects of water, is believed to protect the western direction. Therefore, placing the structure in the western or southwestern direction was not an acknowledgement of Varuna's authority over water-related matters but also a way of seeking the deity's blessing for an abundance of this vital resource. In the Rajasthan region, the baori (stepwell) stands as a remarkable example of water structures, dating from the 9th to the 18th century CE.

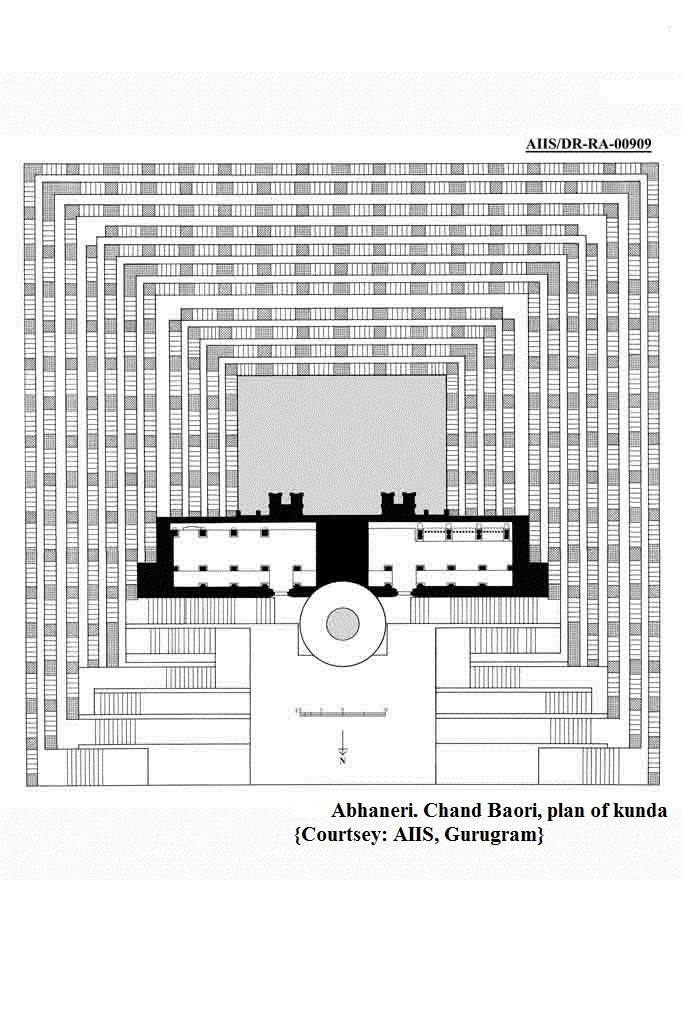

Constructed contemporaneously, the Chand Baori stands southeast of the Harshatmata Temple. Based on the characteristic features mentioned in the Aparajitapriccha, we can classify it as a vijaya-vapi (literally translated: stepwell of victory; architecturally accessible). The stepwell was built in grey sandstone quarried from the Alwar district. It is square and features thirteen-level staircases arranged in a pyramidal shape, which provide steep openings to traverse up and down at the same time. The entrance faces north (Image 1). Based on the construction periods, we can divide the kunda (tank) structure into two parts. The ancient structure has a circular well shaft, flanked by pavilions, and is accessible via stairs. This lower structure includes a wall facing the step, as well as two storied corridors with ruchaka (square) pillars carved with elaborate foliate patterns. ‘Inferior quality’ reliefs depicting a seated Gajalakshmi and standing Parvati are present on the kakshasanas (seatbacks). The pillars alternate between abstract foliate and flower motifs, interspersed with ghatapallava (vase-and-foliage) motifs, similar to those found at the Harshatmata Temple. Remains of large jalis (lattice screens) are still present at the eastern end of the pavilion. An elaborate lattice depicting a flowering vase is also present in the Mughal superstructure staircase (Image 2). The northern wall, which faces the stepwell, features two projecting offsets with small niches that resemble shrines with phamsana (pyramidical) roofs. The west and east shrines, respectively, house sculptures of Ganesha and Durga Mahishasuramardini (Images 3 & 4). An empty niche is present at the extreme ends of the projecting offsets. These offsets are located in a rectangular block, which features a small ribbed dome crowned by an amalaka (crowning member) and a spherical kalasha (pitcher, torus moulding) flanked by makaras (mythical sea monster). Shaded niche shrines of Shiva-Parvati and Durga on a lion are present above the offsets.

This section dates back to the 9th century CE. The superstructure displays an amalgamation of the late Mughal and local styles, dating back to the 18th century CE. A high boundary wall encloses the stepwell, with the entrance facing north. A flat terrace surrounds the structure, where a meshed enclosure currently houses loose sculptures from the Harshatmata Temple and the site. The 18th-century structure has two levels, with the lower one resting directly above the earlier structure. Two flights of stairs at both ends lead to the colonnaded, spacious room with cusped arches and the 'palace'. The arcade has a four-sided design and pointed arches. It is also known as the'summer palace’ (Image 5).

It is important to note that the architecture of this period reflects a blend of local Rajput elements with the established Mughal style. There was close interaction between the Mughal court and the Rajput areas, with the Rajputs breaking away from the empire in the 18th century. According to B.M. Alfieri, incorporating the Mughal imperial style into local features symbolized Rajput sovereignty. [2] The movement of artists seeking patronage from the central Mughal court toward emerging regional centres also contributed to the development of this hybrid architecture. The tapering columns with the floral bulbous base prevalent in the upper structure of the stepwell became stylistically entrenched after Aurangzeb’s reign. Festooned arches with 11 to 13 scallops carved along the edge, along with chattris (umbrellas), are commonly associated with 18th-century architecture in Rajasthan. [3] Another notable feature was the addition of an open summer house (kiosk) with pillars and endless scalloped arches for windbreaks. Chand Baori's upper level, therefore, unmistakably belongs to the late Mughal-Rajput style. Morna Livingston, in her seminal work on the history of stepwells, describes the baori as'showing two classical periods of water building in a single setting’. A shaft for cross-ventilation is situated at the back, originally used for hauling water for cattle but currently blocked with sand. Small, plain jalis adorn the windows.

The involvement of large-budget media projects, such as using monuments as sites for film shoots, not only boosts the popularity and consequently the tourism of the water structures, but also raises awareness of the sites and facilitates their renovation. The stepwell in question, the Chand Baori, has featured prominently in Hollywood movies such as The Fall (2006) and Batman: The Dark Knight Rises (2012). In a recent economic study, Alka Jain states that the large influx of both foreign and Indian tourists contributes to the financial resources available for the upkeep of the stepwell. [4] Additionally, the revival of these stepwells as public dining spaces, exemplified by 'The Stepwell Cafe' in Jodhpur, revitalizes the Toorji Baori and the Rawla Narlai fine-dining experience, while also incorporating cultural programs into these structures. However, myths, beliefs, and practices imbue the Stepwells with social significance that surpasses their media appeal. After decades of neglect, this kind of engagement with the stepwells rescues a select few from disrepair. Nonetheless, questions persist regarding their viability as structures for water management.

The Chand Baori stepwell served as a water source and bathing spot for the local community until it was placed under ASI protection. It is currently open to the public during the Gangour, Jal-Jhulani Ekadashi, and Abhaneri festivals. Jal Jhulani Gyaras, or Ekadashi, is a popular celebration observed in various parts of Rajasthan during the month of Bhadrapada (August-September). The Jaipur court's paintings also document this Ekadashi celebration. One of the paintings depicts Krishna in a boat, symbolizing the act of carrying the idol across the Talkatora Lake from the Jagat Shiromani Temple during Sawai Jai Singh II's reign. [5] During this festival, the zenana made offerings to 'Thakurji', according to historical records. Today, the Chand Baori continues to celebrate the festival in a manner reminiscent of the 18th century CE. This is one of the times when Chand Baori's water is made available to the public to bathe the Krishna idols, which are then ceremoniously carried back to the Gopalji temple at Abhaneri. This event marks the occasion when Lord Vasudeva turns during his annual sleep, known as Devshayani Ekadashi.

The cultural festival at Abhaneri, also popularly known as Abhaneri Festival, is a government initiative. Since 2008, the festival proudly showcases the local heritage from September to October. Activities such as craft competitions, rangoli displays, camel rides, and puppet shows make for a fun-filled schedule. Folk performances like Kacchi-Ghori, Kalbeliya, Ghumar, and Bhawai, along with ethnic music and food, draw tourism to Abhaneri. Langa [6], singing, and ras lilas [7] are also very popular at the festival. These songs still have elements of bardic narration. There is also a local belief that the festival invokes the monsoon. The Chand Baori and the Harshatmata Temple are an acknowledgement of the longevity of cultural traditions and a testament to the living traditions of the site.

Footnotes:

[1] Dhama, ‘Rajputana and Central India Circle,’ 128.

[2] Alfieri, Islamic Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 282–283.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jain, ‘Spiritual Marketing in Abhaneri,’ 17–20.

[5] Sachdeva, Festivals at the Jaipur Court, 76.

[6] Folk music of the Langa community of Rajasthan.

[7] A folk dance form composed around the mythological stories of Krishna. The dance form primarily originated in the Braj region and eventually became popular in the surrounding regions.

Bibliography:

Alfieri, Bianca Maria. Islamic Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2000.

Dhama, B. L. Annual Report on Rajputana and Central India Circle. Archaeological Survey of India, 1925-26.

Jain, Alka. ‘Spiritual Marketing in Abhaneri: A Case Study Harsad Mata Temple.’ IOSR Journal of Business and Management 17/9 (2015): 17–20.

Sachdeva, Vibhuti. Festivals at the Jaipur Court. New Delhi: Niyogi Books, 2014.