The Demonic King who Lost His Virility: The Cave of Gokarna and the Bisaldeo Temple

By Anchit Jain

पहुर रात पाक्किली । राज आए डेरा मधि ॥

वढिय काम कामना । भई पुरिषातन की सिधि ॥

प्रातकांत करि न्हान । घेन विपन कों दीनी ॥

पंचाम्रत धूप । दीप सिव सेवा कोनी ॥

तिहि बार हुकम देवल करन । पुरन बसाइ बीसल धरुह ॥

संगाइ हस्ति असवार हुइ। फिरयौ राज घर आतुरह ॥

It was the last watch of the night, and the king [Visaldeo] returned to his tent. His erotic desires increased, and the [lost] virility returned to him. Extremely pleased with this, he bathed in the morning and presented a thousand cows to Brahmans. Then he worshipped Shiva [of the Gokarna Cave] with Panchamrita, incense and lights. Then, he ordered the erection of a temple [Bisaldeo Temple] and the construction of the town of Visalpura. Calling for an elephant, he seated himself upon it. Hastily, he returned to his home [to satisfy his amplified sexual thirst] …

The 12th century CE Bisaldeo Temple, situated at the side of the Banas river, near the village Bisalpur in the Tonk district of Rajasthan, is said to have been built by the King Vigraharaja IV or Bisaldeo of the Chauhan dynasty (Image 1). The town is referred to as Vigrahapura in an inscription on a pillar inside the mandapa (pillared hall) of the temple, dating back to 1187 CE (1244 VS) during the reign of the famed Chauhan ruler Prithviraja. The account quoted above of the Bisaldeo Temple and Vigraharaja, to be discussed in greater detail later in the passage, comes from a late medieval bardic account of King Prithviraj, Prithviraj Rasau, purportedly written by his court poet Chand Bardai. However, it was likely written in the 16th century. Full of mythical and quasi-historical accounts, the tale largely deals with the story of this famed king, and the only other ruler of the Chauhan dynasty focused on in the text is King Vigraharaja IV, also called Bisaldeo. He was certainly one of the most important rulers of this dynasty, who founded several towns in his name, including Bisalpur. The Prithviraj Rasau provides an interesting account of how this ruler and the temple he patronized were remembered and the way legends around them, no matter how imaginative they are, were circulated in the medieval centuries. These legends connect the ruler and the temple with the sacred and natural landscape of Bisalpur because of the continued importance of the Shiva linga at the Gokarna cave of Bisalpur, also called the Gokarneshwar Mahadeva. Unlike the Bisaldeo Temple, this cave temple is still active in worship. Thousands of pilgrims flock to the site every year to have darshana (paying homage) of the Gokarna deva and enjoy the natural landscape of Bisalpur.

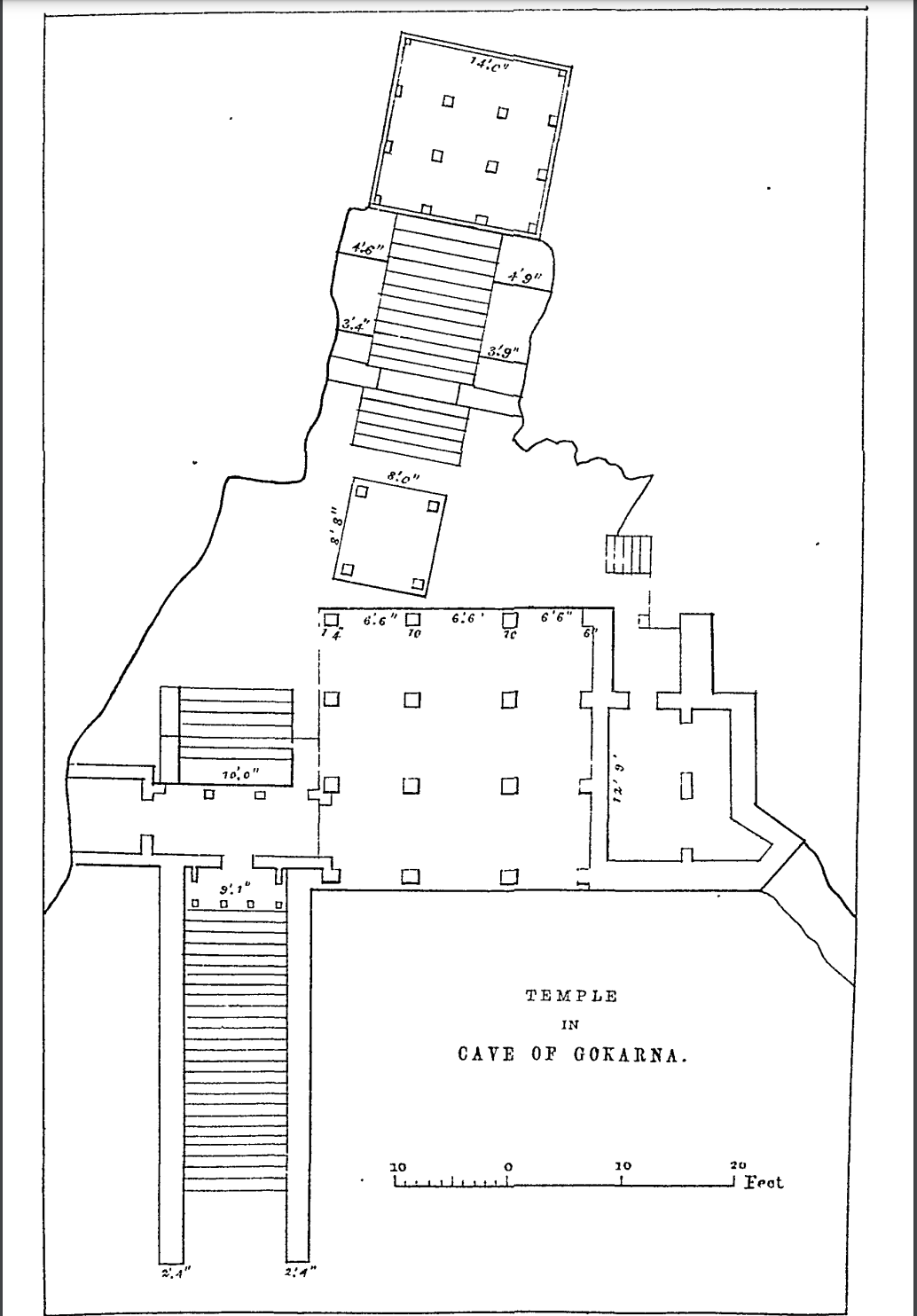

The essay aims to understand the historical associations between the Gokarna cave and the Bisaldeo Temple and explore the after-lives of these associations in the late medieval bardic accounts and the modern mahatmaya literature. In 1871–1872 CE, A.C.L. Carlleyle drew the layout of the temple in the cave of Gokarna (Image 2). The temple had undergone significant renovation by that point, but it remains largely the same despite structural additions and renovations over the past few decades. He described the shrine as:

…a cave temple, or rather a cave, in which temples or shrines have been built, within a two-storied screen or facing of masonry in the face of the rock, in the side of the mountain at the entrance to the pass, immediately opposite to the town of Visalpur…. But with the exception of the bases of some of the pillars (which appear to be older than the rest), the whole of the structures in the cave appear to be modern… [1]

At the apex of this built-in structural complex inside the cave is the much-revered Shiva linga, the Gokarneshwar Mahadeva or the lord Gokarna.

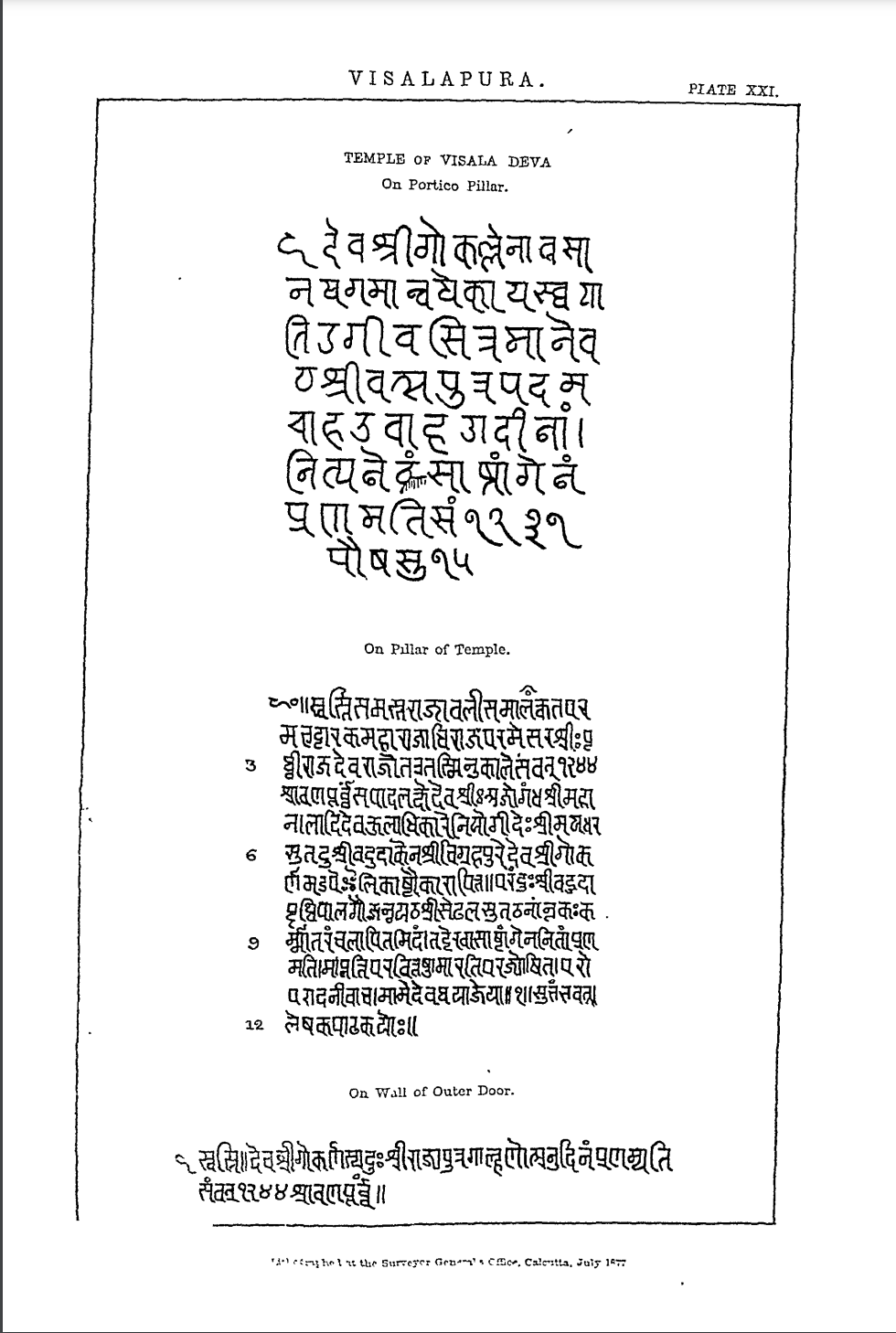

While the origins of the belief of Gokarna are impossible to trace, its sacral importance seems to have preceded the construction of Bisaldeo Temple in the 12th century, as evidenced by epigraphic and late medieval bardic accounts. The Bisaldeo Temple is referred to as the shrine of Gokarna Deva in its inscriptions. An inscription on a left-hand pillar in the vestibule of the temple, dated 1187 CE (1244 VS), during the reign of Prithviraj Chauhan, refers to the hall of this temple as Shri Gokarna mandapa. Carlleyle had highlighted two more short inscriptions from 1174 CE and 1187 CE (1231 VS and 1244 VS, respectively) on the same pillar and on the left side of the entrance of the temple, which also refers to Shri Gokarna. (Image 3)[2] At the time of its construction, the Bisaldeo Temple seems to have derived its sacrality and nomenclature from the older cave shrine of Gokarna. This is further corroborated by medieval Bardic accounts. The Prithviraja Rasau clearly states that Vigraharaja IV had the structural temple (Bisaldeo Temple) erected at the site after his wishes were fulfilled by siddhas of the lord Gokarna, who were pleased with his devotion to the cave.

Prithviraja Rasau paints a comical description of King Vigraharaja IV, whose misfortunes brought him a loss of virility, which he regained after worshipping Gokarna deva. But the boon soon turned out to be a bane that possessed him with an uncontrollable sexual drive, finally leading to him transforming into a demon!

‘King’s absolute love for his chief queen, simply called the Parmar’s daughter, brought extreme jealousy to his other wives. In their anger, they devised a plan to bereft the king of his virility with the help of a yogini. The grieved king, having lost his “manliness”, went to Pushkar to bathe in the holy month of Kartik but was instructed to rather visit the country of Gokarna to worship Shiva for restoring his virility. He visits the cave shrine and showers praises on the glory of lord Shiva. The Siddhas of Shiva, being pleased by the virtues and devotion of the king, narrate the mythical history of the shrine and grant him what he was yearning for the most, kāma or erotic desire. King Vigraharaja, having his virility returned, presented a thousand cows to Brahmanas and elaborately worshipped the linga of Gokarneshwara deva. In this wild natural landscape of the Gokarna country, he decided to construct a town, Bisalpur, named after him and erected a grand temple of Shiva [the Bisaldeo Temple].

He rushed back to his home to quench his sexual thirst, but all his wives failed to do so. His kama increased day and night, and he lost his control. Women of all ages and wives of men of all varnas began to tremble at him. He leaves none on whom he casts his eye. The king decided to divert his energies into reckless warfare but eventually ended up molesting a bania’s daughter who was performing austerities in Pushkar. The girl cursed him to convert into a human-flesh-eating demon. In his aghast, he rushed back to the Gokarna shrine and decided to repair it. Alas, he was bitten by a snake in his tent and, before he could do anything, was converted into a man-eating demon. His terror among his subjects was finally over when he was subdued by his grandson in combat, and he finally retreated to various tirthas to perform austerities and finally left his body at Kashi after receiving a boon from Shiva!’ [3]

In complete contrast to this ludicrous legend, Vigraharaja IV was a famed ruler of the dynasty whose military and other achievements resulted in Dashrath Sharma referring to his reign as the ‘golden age of Sapadalaksha.’ Fortunately, the availability of at least 11 inscriptions of him (verses 1210–1220) gives a better representation of his reign.

He was the son of King Arnoraja, an aggressive warrior and ambitious ruler who had spent most of his reign in warfare but was ultimately defeated by the Solanki (Chalukyan) king of Kumarpala of Patan. As per the medieval chronicle, Prithivirajavijaya, Arnoraja was murdered by his eldest son Jaggadeva, whose short rule was, in turn, ended by his brother Vigraharaja IV in a battle. He soon embarked on several retaliatory expeditions against the Chalukyas to avenge the defeat and humiliation of his father. He expanded his dominion far beyond the region of Sapadalaksha after defeating various Chalukyan vassals of Rajasthan, rebuffing Muslim invaders and capturing Delhi from the Tomar and converting them into complete feudatories. His military exploits are glorified in Sanskrit eulogistic texts like the Prithvirajavijaya and Lalitavigraharaja. The latter is a classical drama written by his court poet Somadeva, celebrating the achievements of Vigraharaja IV. [4] Unfortunately, the text is available in only minor fragments, and the late medieval bardic accounts obliviate his achievements with the ludicrous narratives. Vigraharaja IV himself did not leave any inscriptions on the temple, but his association with the city he established and the temple far bypassed his heroic legacy.

Apart from Prithviraja Rasau, another late bardic account, Bisaldeva Raja Rasau of Narapatinalha, provides a different anecdote of the Bisaldeo Temple construction. It states that King Ajayapala had two sons, Anadeva and Bisaladeva (Anadeva was Bisal’s father in Prithivarajavijaya), and both inherited 20 crores each. While the former built the Anasagar lake at Ajmer, the latter chose to erect this temple with the money. However, his military achievements did not permit him to finish the work. [5]

Vigraharaja’s contribution was not just limited to erecting the Bisaldeo Temple but to firmly placing this older settlement and sacred centre into the broader religious, political and economic nexus of the Chahamana territory. Based on oral legends and some fragmentary archaeological remains, Carlleyle was of the view that an older settlement, Vanapura, was already in existence before the erection of the temple. [6] Vigraharaja, however, built a new town here and also extended the sacrality of the site outside the Gokarna cave to his temple, which was also named the Gokarna temple. The broader integration of the temple into the regional political and economic configuration is corroborated by several short inscriptions recorded by visiting merchants and feudatories. The temple lost its glory with time, but the worship of Gokarna, which preceded the Bisaldeo Temple, continues to date. Emerging literature around the cave shrine, like the recent Shri Gokarneshwar Mahadeva Mahima, attempts to convert the temple into a Puranic site and aims to cement the longevity of Shaiva devotion at Bisalpur.

Footnotes:

[1] Carlleyle, Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana, 155.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Summarized account of the English translation of the first cantos of Pritiviraja Rasau, in The Indian Antiquary, Vol.1, 1872, 271–279.

[4] Sharma, Early Chauhan Dynasties, 56–62.

[5] Parashar, Shri Gokarneshwar Mahadeva Mahima, 28.

[6] Carlleyle, Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana, 153.

Bibliography:

Beames, John. “Translation from the First Book of the Pritiviraja Rasau.” Edited by James Burgess. The Indian Antiquary 1(1872): 269–82.

Carlleyle, A. C. L. Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1871-72 and 1872-73, by A.C.L. Carlleyle ... Under the Superintendence (and with preface) of Major-General A. Cunningham ... Edited by Alexander Cunningham. VI. Reprint. New Delhi: The Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, 2000.

Sharma, Dasharatha. Early Chauhan Dynasties: A Study of Chauhan Political History, Chauhan Political Institutions and Life in the Chauhan Dominions from 800 to 1316 AD. Jodhpur: Books Treasure, 1959.

Pandia, M. V., R. K. Das, and S. S. Das. eds. The Prithiviraj Raso of Chand Bardai, Vol. 1. Medical Hall Press: Benares, 1904.

Parashar, Jiwanshankar. Shri Gokarneshwar Mahadeva Mahima. Laxmi Pustak Bhandar, Deoli.