Contextualizing the Shaiva Imagery of the Bisaldeo Temple

By Anchit Jain

The Bisaldeo Temple is a 12th-century CE temple dedicated to Shiva, which is situated at the side of the Banas river, near the village of Bisalpur in the Tonk district of Rajasthan. Bisalpur is a centre of religious pilgrimage to the shrine of Gokarneshwar Mahadeva, a cave-turned-structural shrine located close to the Bisaldeo Temple. While it is difficult to date the origins of this Shiva cave-shrine, and this linga (an aniconic form of Shiva) is considered to be the self-manifested one or the svayambhu or self-manifested, it was certainly much older than the Bisaldeo Temple. The latter was likely to be built by King Vigraharaja IV or Visala Deva (Bisaldeo) of the Chauhan dynasty as a state-supported shrine in the already sacred landscape of the Bisalpur, next to the local water body. This new structural temple derived its sacrality from the old Gokarna cave and its religious landscape, and thus, even the lord of the Bisaldeo Temple was called the Gokarna deva, as appears from the contemporaneous epigraphs. [1]

To the disappointment of many, the temple walls are bereft of any imagery, nor do we have a significant number of notable religious images inside the temple. Yet, the limited images can be decoded to understand the Shaiva religious milieu of its times. The lintel of the sanctum-doorway shows a two-armed depiction of Lakulisha seated in padmasana (lotus pose) in dhyanmudra (the hand seal gesture for meditation), carrying a lakuta, or club, in his left hand and fruit in his right hand—part of his standard iconography—inside a niche on the lalatabimba (lintel) on the dvarashakha (doorjamb) (image 1). On either side of the lintel are four-armed depictions of Brahma on the left and Vishnu on the right. Replacement of the image of Shiva with Lakulisha at the lintel niches of the sanctum doorway was once a common feature of the Pashupata tradition. This is one of the earliest communities of Shaiva devotees, who claimed their ascetic lineage from Lakulisha, a human-ascetic manifestation or avatara of Shiva. The early sections of Skandapurana (550–650 CE) provide important information about this myth of Shiva’s human descent and the traditions associated with it. The story begins in a place called Karohana, located in Karvan in modern-day southwest Gujarat, where Shiva was reported to have descended to earth in every cosmic age. The avatara of this age was a teacher, Lakulisha, who disseminated Pashupata knowledge through four pupils, described as brahmins produced from Shiva’s four mouths. [2] The Pashupata tradition gained significant popularity during the early medieval centuries throughout the subcontinent. Each ascetic order in this tradition traces its lineage from one of these four disciples of the divine founder.

In the ancient cities and towns of Rajasthan, of the various traditions of Brahmanism, Shaivism found the greatest acceptance and was quite prevalent even during the Kushana and Gupta times. Of four major Shaiva sects, Shaivasiddhanta, Kaula, Kapalika and Pashupata, it was the Pashupata tradition that had a visible influence in the region from the 7th century onwards. Having received patronage from various local clans, the Pratiharas, the Chauhanas and the Guhilas, among others, the Pashupata ascetics often wielded strong political power. [3] The 12th-century Bisaldeo Temple is inextricably linked with the Chauhan ruler Vigraharaja IV, or Bisaldeo, both through its name as well as the oral legends and the medieval and early modern bardic accounts like the Prithviraja Rasau of Chand Bardai and Bisaldeva Raja Rasau of Narapatinalha. However, this strong political association should not subsume the role of Pashupata ascetics, who had stamped their sectarian affiliation on the doorway of the sanctum of the shrine. The 10th-century Harshnath Temple at Sikar provides much older evidence of a strong nexus between the Chauhana politics, the influence of Pashupata ascetics and the temple construction. The Pashupata ascetic Allata is celebrated in verses 33–34 of the stone inscription of the Harshnath Temple, which was built ‘with the wealth received from the pious people.’ [4] Simultaneously, various rulers drew the legitimacy for their ritualized sovereignty through grants and patronage to this temple, as described in verse 18. [5]

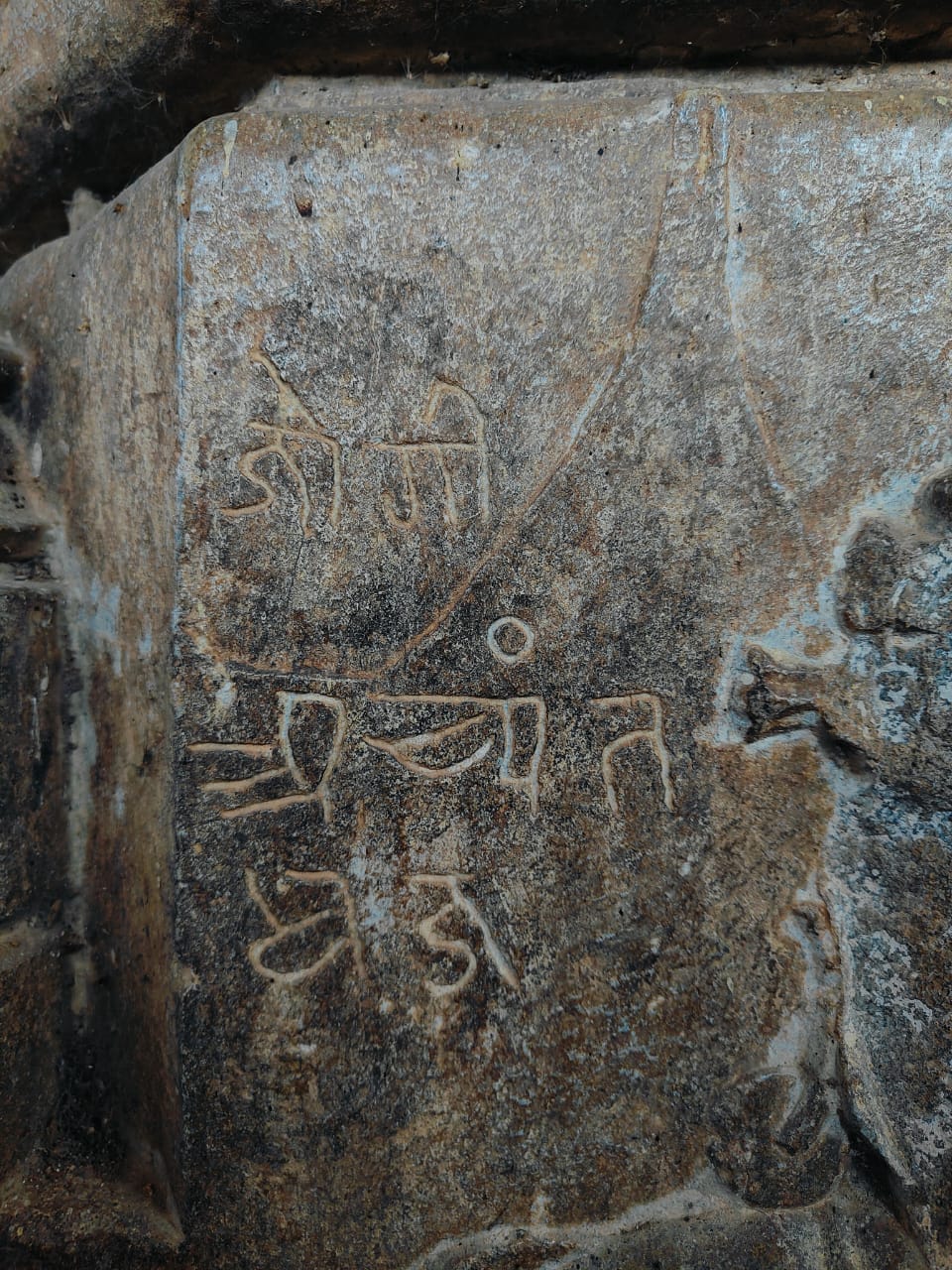

Unlike this temple, the Bisaldeo Temple lacks any notable inscription attributable to the Pashupata ascetics, but it still seems to hint at their influence. On one of the pillars of the temple is a short inscription which mentions the name Jogi Achpantadhaja or Yogi Achintyadhvaja (Image 2), inscribed next to an image of an interesting damsel [6] (Image 3), revealing the influence of a monk, likely belonging to the Pashupata tradition. His name, Achintyadhvaja, meaning the ‘sign/flag of the incomprehensible one,' is an interesting one. The grand Shiva linga, 7.3 feet in height, at the 11th century Bhijeshwar Temple, Bhopal, has the Sanskrit word Achintyadhvaja inscribed on its pedestal. [7] The grand Shiva linga is also referred to as the sign/pillar of the incomprehensible one (Shiva), and perhaps the yogi (ascetic) was seen as the body of the Shiva tattva (principle) and carrier of the legacy of Shiva’s human manifestation.

While beautiful damsels usually occupy the space on the shaft of the pillars, the pillars closer to the sanctum also have images of male Shaiva devotees, both ascetics and royalty. Some of these images were inscribed at the bottom with an inscription of later centuries. For instance, an ascetic is shown on one of the pillars with a long beard and what seems like a jata. A kamandalu (pot) is tied to one of his shoulders through a rope. He wears nothing but a kopina (loincloth), and the janeyu (sacred thread) is shown quite prominently (Image 4). The janeyu reminds the viewer that the lineage of ascetics in the Pashupata sect has been predominantly Brahmins right from the time of Lakulisha and his four disciples. Even Lakulisha has been depicted elsewhere in this temple with a prominent janeyu (Image 5). The bare minimum clothing and kamandalu are signifiers of his asceticism. The Harshnath stone inscription mentions the naked Shaiva ascetics of the Pashupata tradition as well as the ascetic Bhattarak Naganaka, who lived in the temple of Somnath at Shergarh in Rajasthan. [8]

There are at least two heavily jewelled royal figures, one holding a garland (image 6) while the other in tribhanga (meaning three breaks, where the body is divided into three parts) with broken hands (Image 7). Whether these are representations of the patron, King Vigraharaja IV, is a matter of pure speculation. Nevertheless, these representations reveal an important characteristic of early medieval Shaivism, where both the ascetics and regional rulers cooperated with each other in the religious and political spheres in an era that Alexis Sanderson vehemently called the ‘Shaiva age.’ Temple epigraphs suggest that various political and economic constituents of the state got involved with the shrine at different stages. An inscription from 1187 CE (1244 VS) records veneration of the lord by Shri Rajputra Galhana, who might have been a feudatory of the Chauhan dynasty. One short inscription on one of the vestibule pillars read ‘Navva Guhilait’, corresponding to an individual of Guhila lineage. [9] Another inscription from 1187 CE (1244 VS), composed during the reign of Prithviraja Chauhan, records a donation by a merchant trader, Setha Thananaka, son of Shri Sedhula. Of course, it is the close association of the Chauhan King Vigraharaja IV that was repeatedly emphasized in the medieval period, with various fanciful stories being fabricated about his relationship with the temple.

As stated earlier, the religious images inside the temple are few, yet these reveal some notable religious layers of historic importance. The only major image depicting the divinity of Shiva on the mandapa (pillared hall) is a four-armed depiction of Bhairava on a temple shaft near the entrance of the temple. It is practically the first religious image encountered as one visits the temple (Image 8). He wears the necklace of a serpent, but other identifying attributes have deteriorated over time. His heavily jewelled naked body clearly reveals his genitalia. The erection of a separate shrine to the fierce aspect of Shiva, Bhairava or Bhairon, is a common feature of various early medieval, medieval and even contemporary shrines. The Chauhan temple at Harshagiri (Sikar), two centuries older than the Bisaldeo Temple, has a separate enclosure dedicated to Bhairon. However, in the absence of any Bhairava shrine at Bisalpur (as per the current evidence), this Bhairava image at the entrance of the shrine might have served the same purpose.

There are several minor Shaiva images on the ceiling and the beams of the mandapa, like devotees worshipping Shiva linga (Image 9), Natesha (Image 10) and Ganesha, among others, but these are minor images interspersed between various Brahmanical images. Likewise, the kumbha (one of the basal mouldings with curved shoulder) niches at the base of the pillars in the mandapa have depictions of various goddesses, as has been a common practice in some parts of the early medieval era in Rajasthan. However, some of them also have figures of ascetics (Image 11 and Image 12), but one ascetic requires special attention, who is no other than Lakulisha himself. Placed in a remote corner facing the southern wall, completely away from the immediate eye of the public, is an image which is a clear testimony of the declining stature of the cult of Lakulisha in western India. Apparently, this minor image, along, with the one on the lintel of the sanctum’s doorway, are amongst the latest depictions of Lakulisha to adorn any historical temple.

In Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape: Narrative, Place, and the Śaiva Imaginary in Early Medieval North India, Elizabeth Cecil discusses historical development in the cult of Lakulisha, where the association of this human-ascetic teacher with Shiva was subject to divergent interpretations in different historical periods. She notes a major transformation in the cult of Lakulisha in the early medieval centuries with two often closely related developments. First, a shift in the placement of icons depicting Lakulisha, which were no longer limited to the sanctum doorway serving as Pashupata emblems. These were also taken to the temple exterior, where he was integrated within the larger pantheon of deities adorning these monuments. Second, his iconography was no longer limited to a distinctly human teacher, rather he was now depicted as a divinised figure that was nearly indistinguishable from Shiva. [10]

Images of Lakulisha from the Harshnath Temple, Sikar, serve as evidence for these developments. While he still occupies his position as a Pashupata emblem in the lintel niches, he occupies notable places on the temple exteriors on the niches of the walls, as seen in one of the images from the site, which has subsequently been placed in the Government Museum at Sikar (Image 13). The four-armed portrayal of Lakulisha is almost indistinguishable from Shiva, who is typically shown with a trident and a jatamukuta (made of twists of matted hair). This depiction represents a high point in the visual depiction of Lakulisha in western and northern India, after which it faced a steady decline. First, his importance was reduced to being a minor, repeated figure of significantly diluted symbolic value until, gradually, these images disappeared from the temples completely. As Lakulisha decreased in popularity, the niche above the sanctum door was commonly occupied by an image of Ganesha. [11]

Given that Lakulisha is depicted as a human-ascetic depiction in the Bisaldeo Temple, it is possible that the trend within the iconography of depicting him as divine or likening him to Shiva was already over within two centuries. He continued his position as a Pashupata emblem at the doorway for some time, but his importance seems to have been greatly reduced. There is no notable image of Lakulisha, unlike Bhairava, and the image that is present occupies a remote position away from the public attention on the pillar bases interspersed with other ascetics and minor goddesses. The Bisaldeo Temple, thus, reflects the declining importance of the belief of Lakulisha, but perhaps also of the Pashupata traditions. Nevertheless, the ascetics of this sect undoubtedly still held sway politically and socially to have had a royal temple and maintained close connections with one of the most illustrious rules of the Chauhan dynasty.

Footnotes:

[1] For an overview of some of the epigraphs of Bisaldeo Temple, see Carlleye’s Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana, 155–156.

[2] Cecil, ‘Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape,’ 286–287.

[3] For an overview of the influence of Shaivism in the region, particularly that of Pashupata, see Jain’s Ancient Cities and Towns of Rajasthan (522–523). For a detailed discussion on a close association between the Guhila politics and Pashupata tradition, see Nandini Sinha-Kapur’s State Formation in Rajasthan: Mewar during the Seventh-Fifteenth Centuries.

[4] Bhandarkar, ‘Some Published Inscriptions Reconsidered,’ 57–64.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Unlike other damsels/apsaras carved on the shaft of pillars, she is the only one crowned and holds a cup in her left hand while the right hand holds something dipped in the cup. Several images from the Harshanath temple complex show a cup being held, signifying the nectar of bliss experienced after the completion of tantric-sadhana, while the fingers of the other hands are sometimes dipped into the cup. However, associating an obscure image of a damsel with some tantric connotations might have little support.

[7] Cunnigham, Notes on the Antiquities of the Districts, 743.

[8] Jain, Ancient Cities and Towns of Rajasthan, 523.

[9] Carlleye, Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana, 155–156.

[10] Cecil, Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape, 212–13.

[11] Ibid., 244–245.

Bibliography:

Beames, John. “Translation from the First Book of the Pritiviraja Rasau.” Edited by James Burgess. The Indian Antiquary 1 (1872): 269–82.

Bhandarkar, D. R. "Some Published Inscriptions Reconsidered. 1-Harsha Stone Inscription of Vigraharāja’." Indian Antiquary 42 (1913): 57–64.

Carlleyle, A.C.L. Report of a Tour in Eastern Rajputana in 1871-72 and 1872-73, by A.C.L. Carlleyle ... Under the Superintendence (and with preface) of Major-General A. Cunningham ... Edited by Alexander Cunningham. Reprint. Vol. VI. New Delhi: The Director General, Archaeological Survey of India, 2000.

Cecil, Elizabeth A. "Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape: Narrative, Tradition, and the Geographic Imaginary." The Journal of Hindu Studies 11, no. 3 (2018): 285–303.

Cecil, Elizabeth A. Mapping the Pāśupata Landscape: Narrative, Place, and the Śaiva Imaginary in Early Medieval North India. Brill, 2020.

Cunningham, J. D. “Notes on the Antiquities of the Districts within the Bhopal Agency &c,” The Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Vol. XVI, Part II July to December 1847 (Calcutta: 1847), pp. 739-744.

Jain, K.C. Ancient Cities and Towns of Rajasthan: A Study of Culture and Civilization. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, 1972.

Nagarch, B.L.'Visaldeva Temple, Visalpur’. In Pathways to Literature, Art and Archaeology, (ed.) Chandramani Singh and Neelima Vashishtha, Jaipur: Publication scheme, 1991.

Sanderson, Alexis. "The Śaiva Age: The Rise and Dominance of Śaivism during the Early Medieval Period." In Genesis and Development of Tantrism, 41–349. Edited by Shingo Einoo. Institute of Oriental Culture Special Series, 23. Tokyo: Institute of Oriental Culture, University of Tokyo, 2009.

Pandia, M. V., R. K. Das, and S. S. Das. eds. The Prithiviraj Raso of Chand Bardai, Vol. 1. Medical Hall Press: Benares, 1904.

Parashar, Jiwanshankar. Shri Gokarneshwar Mahadeva Mahima. Laxmi Pustak Bhandar, Deoli.